1942: Radio School - The Navy Comes to Madison

Early 1942 Plans for a Radio School

In January 1942, Ninth Naval District Headquarters notified Dykstra that it had forwarded Morgan's inspection report to the Bureau of Navigation to recommend that the Navy establish a “Radio Material School” for 500 men, increasing by 1000 on 1 June 1942. Dykstra at once wrote an enthusiastic reply requesting specifics on instructional force requirements. No shrinking violet, Dykstra added, “...it might be possible for us to increase to 1000 on June 1 by a considerable number if that would seem desirable. We would simply require students to find accommodations off the campus.” Anxious for a favorable reply, Dykstra wired Navy Secretary Frank Knox requesting his support and noting the roles the university was already playing in the Civilian Pilot Training program and in cooperating with the Navy's V-7 enlistment program. He added, “We are anxious to be of service and will be happy to be designated for the Radio School. Will you help us to help you?” In late 1941, Dykstra had agreed to serve in Washington part-time as director of the draft administration. He had studied political science and had practical political experience as city manager of Cincinnati. Thus, he knew how and actively sought to pull the levers of political influence to acquire the radio school (he was equally willing to take similar actions for V-12 and NROTC).

On 20 February 1942, the Commandant of the Ninth Naval District, Rear Admiral John Downes, informed Dykstra that he had his school. It was a “Naval Training School (radio)” for training radio operators, with a maximum capacity of 1200 men to arrive in increments of 300 per month for the sixteen-week course. The university was to furnish dormitory facilities and messing for students and Navy active-duty staff, plus utilities, maintenance, care of grounds, and laundry. The Navy would provide beds, mattresses, lockers, linen, blankets, towels, mess trays, cups, bowls, glasses, and silverware. The university also provided classrooms, instructors, and equipment to provide instruction similar to that already in effect at a Navy radio school in Indianapolis. Finally, the Navy would contract with the State of Wisconsin General Hospital for infirmary and hospital care while supplying naval medical and dental officers and personnel. Contracts would cover all aspects of the agreement. The first group of students was scheduled to arrive on 1 April.

A Navy Push for Technical Training of Officers

In January of 1942, at a Baltimore conference, the Navy called upon the colleges and universities of the country to stress technical training for students about to enter the service and to realize their responsibilities for advising students about their options of volunteering for enlistment, continuing their education under V-7 or V-5 (aviation training), or seeking degrees in engineering. The Navy also recommended curricular acceleration. As matters progressed, colleges and universities became part of the system for providing officers to the armed forces.

Within a month of the announced revision to V-7, the Navy created another class of enlisted men (V-1) who would remain in inactive status while enrolled in college. V-1 was open to men 17 to 19 years of age willing to attend college at their own expense until the completion of two academic years. They could study any academic curricula acceptable to the Navy and were to stress physical training, mathematics, and the physical sciences. The Navy hoped to procure about 80,000 men in V-1. Near the end of the third semester, V-1 students would take a qualifying examination, and, upon completion of their fourth semester, approximately 20,000 would transfer to flight training (V-5), and 15,000 would transfer to V-7 (5,000 of these to be engineering students) to continue their education. The remainder, over half, would commence active duty as apprentice seamen. Somewhat obviously, V-1 never generated any great appeal to college men. Less than half of the desired 80,000 enlisted, and the program failed to become popular despite several liberalizing changes.

American and Phillippine Troops Surrender at Batann, April 1943

Madison Becomes a Navy Town Spring 1942

February and March were hectic months. The Regents blessed the project and provided the funds needed for preparations. The university pressed the work in the stadium to completion, conditioned the agriculture Short Course halls for temporary Navy housing use in April and May, made needed changes in kitchens and dish rooms, and prepared and signed contracts. Classroom and academic staff preparation continued apace. The university projected an initial instructional staff of about ten, expanding with successive increments of students to approximately 30, teaching code, typing, mathematics, radio and electronic theory, radio laboratory technique and spelling. Plans included the eventual use of the Adams and Tripp dormitories as well as the space being prepared in the stadium.

On 1 April, the Fleet steamed into Madison - by train. Three hundred sailors, mostly apprentice seamen and seamen second class, descended upon the campus and the university went on "active naval service.” It was quite an event, and the excitement spread over the next few days. The Wisconsin State Journal greeted the sailors, “We’re glad you’re aboard, gentlemen.” The young men also endured in good spirits official welcomes from Dean George C. Sellery and Mayor James R. Law. The new Officer-in-Charge, Lieutenant Schubert, cautioned them, “Don’t disgrace your uniform.” Professor Miller introduced the educational staff and the sailors politely applauded, but they reserved the biggest outburst for the truly most important person, the Navy paymaster. Next came Good Friday services and class assignments.

The Saturday morning schedule included military classes and open-air military reviews. Saturday afternoons were dedicated to sports and recreation. Sundays included church, study, and liberty. The intensity of the training schedule reflected the urgency of America’s commitment to the war.

These early days were heady, at times confusing, and even tense. The university had to master Navy language (mess, galley, deck, head, watch, etc.). Residence hall director Halverson had to carefully document, for a Navy staff officer, Lieutenant Boudry, the policies, procedures, and personnel supervision exercised by the university in procuring and preparing meals for the sailors. Nevertheless, given the chaos of starting a program quite unlike anything ever done before on the Madison campus, things probably went better than could be expected. The experience was equally new for the Navy because the Wisconsin Radio School was the first one located on a college campus. In May the new school received its initial Navy inspection by Lieutenant Robert W. Percy of the Bureau of Navigation. Percy was impressed with all aspects of the school, and he expressed confidence in the abilities of its prospective graduates.

Scarcely was the new school into its post-commissioning “shake-down” when President Dykstra received a confidential letter from Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs, Chief of the Bureau of Navigation. Jacobs disclosed the Navy's proposed legislation which would authorize enrollment of women in the Naval Reserve for specialist duties which would relieve men for service in the fleet, and he wanted to know what capacity the university might have for the assignment of women trainees. Dykstra’s reply was typically enthusiastic and indicated a capacity for 600 women on 1 June, and there was the possibility that “after we have had experience with these and know a little bit more about the load we will have to carry during the next academic year we can take more.... Perhaps I may be pardoned for making the suggestion, then, that the Navy give consideration to the setting up of a radio and communications unit for women upon the theory that there will be no unnecessary duplication of facilities by such a process.” Dykstra would later regret this action because he was unwittingly digging the university deeper into a situation at variance with its interests. However, early war euphoria still influenced events.

V-1 Program Begins

In early 1942 the Navy announced V-1, and the University of Wisconsin eagerly sought to be accredited for the program. In March, by letter, the Navy formally approved, under V-1 guidelines, the curriculum outline submitted by the university, thereby permitting participation in the program. That letter additionally requested active recruiting support.

On 10 April Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox telegraphed a message of congratulations and solicited recruiting assistance. These messages not only raised President Dykstra’s spirits, but also led him to believe that the university’s status as a land grant school, with compulsory ROTC enrollment for freshman and sophomore men, was not an impediment, and he immediately launched an active recruitment campaign to encourage eligible prospective students to enroll in V-1 and the university. However, the land grant issue soon became a matter of real concern.

Japanese Army troops celebrate the fall of Corregidor May 1942

May 1942 V-1 Off to a Rocky Start

On 6 May, Dykstra received a letter stating that the Navy could not promote naval enlistments in land grant colleges. He immediately wrote to the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, insisting that the Regents had full authority to exempt freshman and sophomore students from compulsory ROTC enrollment. Thus the Navy should not feel any impediment to V-1 accreditation. He asked, "May we have a directive sent...indicating that the University has been accepted, both by your office and by the Secretary of the Navy? ...Because of the acceptance which we had from your office, we have notified the high schools throughout the State of this program, and many students on the campus are waiting for an opportunity to enroll.”

Although it took some time for its bureaucracy to react to this plea, the Navy finally resolved the matter in the university's favor by late June, and the crisis passed. V-1 failed to attract widespread popularity, and, on the Madison campus, the Radio School was already showing signs of failing to live up to Dykstra’s expectations. Thus, at the end of 1942, the announcement of the proposed Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) and the Navy College Program (V-12) immediately caught his attention. He informed the faculty about the structure and potential of both programs.

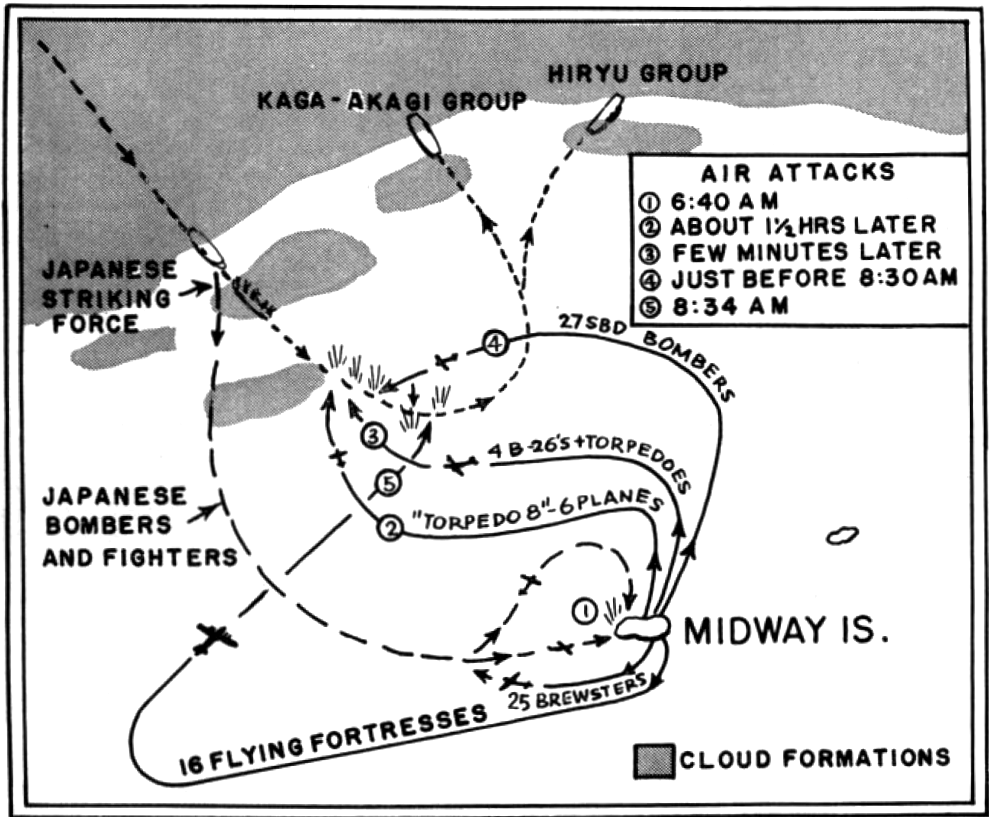

TBDs on USS ENTERPRISE (CVA 6), Battle of Midway, June 1942

Battle of Midway Air Attacks

Early Crisis in the Radio School Program

Signs of potential trouble first appeared in May when the Ninth Naval District Training Director advised commanders of naval training schools that a review of synopses of courses being offered indicated several cases of significant deviation from “previously established curricula.” He cautioned them to “ascertain that the courses of study established conform, insofar as is practicable, with the approved courses....” Several days later, radio school instructional director Miller warned Dykstra of a staff “crisis” caused by a deficiency in the number of sea-experienced chief radiomen assigned by the Navy to the school. The need was great because “only chiefs who have had some sea experience can meet our needs, as only they would know what would be required to fit the men for sea duty.” Although no one was prepared to say it bluntly at that point, the signs were clear that schools such as the one at Madison needed considerably more Navy supervision and control.

Dykstra wrote to the Ninth Naval District Commandant to get the chief petty officers needed to be assigned. By June, no chiefs had arrived, so Miller again wrote to Dykstra about the problem, now asking him to write directly to the Bureau of Navigation and request assignment, not of the two or three previously desired, but of one chief or first-class petty officer for every 100 students, for a sizeable increase in ship’s company, and even for a recreation officer!

School-community relations also suffered. In mid-June, the Regents agreed to declare campus areas occupied by the naval trainees as naval reservations, excluding the public from them (Camp Randall Stadium, Adams and Tripp dormitories, and the intramural fields from the dormitories to the Stock Pavilion). “Keep Off—Naval Reservation” signs appeared, and officer-in-charge Schubert solemnly stated, “People must realize that we are at war and that this is a naval camp in which we are training men for active war duty.” In reality, however, the action taken was for less profound purposes. It was a reaction “to a series of insidious rumors which have circulated the city recently involving the morals of sailors attending the U.S. Naval Training school...and Madison high school girls.” Although a volunteer investigating committee declared the charges to be unfounded, posting of the areas was done “to help us carry out our work and to cooperate with city officials in adjusting the program to community relations.” This was at least one radio school crisis that went away.

Radio School Graduates its First Class

Despite these problems, the school managed to move forward, and on Sunday, 26 July 1942, 248 sailors graduated from an outdoor ceremony in the stadium. Sixty of them were honor graduates and won their “crows,” rated radiomen third-class. President Dykstra saluted the graduates with a ponderous “Wisconsin bids you farewell and God speed. From this moment on you are a part of the Wisconsin tradition of hope, of fair play and of elementary justice.” A slightly less Olympian message, and one somewhat more to the point in the eyes of the service men, was sponsored by a number of Madison businesses and appeared in the campus newspaper: "GOOD LUCK, SAILORS AND CONGRATULATIONS FROM ALL OF MADISON! Give HITLER, HIROHITO and MUSSOLINI HELL for us...."

Naval Training Schools Command Class Graduation, ca. 1942 -1945, Camp Randall, Madison, WI

Now the school was at full strength. Based on positive comments from the Navy concerning the probable assignment of Naval Reserve women to the university, the Regents authorized the president, comptroller, and the executive committee the power to act to use Chadbourne and Barnard Halls as living accommodations for 450 to 500 “girls.” In early August, the Navy formally advised the university of its selection as “a training School for enlisted radio operators of the Women’s Reserve, United States Naval Reserve.” Instruction was to commence on 1 November 1942 for 470 women. The assignment of the WAVES increased the need to centralize code instruction and focused even more attention on the Blackhawk Garage. J.L. Miller was already feeling considerable anxiety over the building by that time because he was attempting to negotiate modus vivendi with the Athletic Department to retain until mid-September at least some Fieldhouse space for code instruction— despite the needs of fall registration and the basketball team. In the meanwhile, the second graduating class from the radio school paraded through Camp Randall on 23 August. Of the 258 graduates, 64 were honor men and were rated. The Radio School was finding an operating rhythm. However, the arrival of the WAVES was to rekindle the dynamics of change.

August 1942 The University Acquires the Blackhawk Garage

In August the university purchased the Blackhawk Garage which it would remodel for use as a central location for code classes (which temporarily were meeting in the Fieldhouse).

A Japanese bomb exploding on the flight deck of USS ENTERPRISE (CV 6), just aft of the island, during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons on 24 August 1942

USS QUINCY (CA 39) illuminated by IJN spotlights prior to sinking, Battle of Savo Island, August 1942

WAVES Assigned to Radio School

The first WAVES Officer arrived in September. She was Lieutenant Dorothy C. Stratton, former dean of women at Purdue. Assigned to the naval schools as assistant executive officer, she was responsible for supervising the training and housing of enlisted WAVES assigned to the Radio School. Lieutenant Stratton would soon transfer to the Coast Guard with the rank of lieutenant commander and head its women's division, the "Spars.”

On 9 October, the arrival of 480 enlisted WAVES, who came aboard as the first women students of the radio school, overshadowed the previous arrival (on 6 October) of Commander Charles F. Greene as Naval Training Schools commanding officer. There was much ado over the arrival of the women, but the stars of the group were the society ladies. Among them was Miss Edith Kingdon Gould, 22-year old great-granddaughter of financier Jay Gould, who "put aside her society life and a theatrical career” and arrived wearing a "gray woolen suit with checked vest and a gray caracul coat.” Other luminaries included Emily Bradley Saltonstall, daughter of the governor of Massachusetts, and Miss Jacqueline Reifsnider, who was born and lived in Japan and who averred that upper-class Japanese “do not like their government or its acts, but can't do anything about it." Their welcome to the campus commenced in earnest on Saturday, 10 October. It included a brief drill and review by Commander Greene and Lieutenant Stratton, meeting the press and photographers, and attending the Wisconsin-Missouri football game.

Happily, there was no follow through on a plan to march the women into the stadium—almost none of them knew how to march! The women arrived in advance of uniforms and they would spend several weeks wearing civilian clothes. The induction ordeal continued on Monday with an orientation program in the Union Theater. Lieutenant Stratton told the group, “We’re not glamour-girls. We’re not here for a good time. We’re here to aid our country.” Commander Greene added, “You are important to the Navy. You have a serious task to perform to relieve the men in the Navy for active duty with the fleet. I welcome you into the Navy. You must uphold Navy tradition.” Other dignitaries speaking were Dean Holt, representing president Dykstra, and Mayor Law. The welcome done; the women commenced three weeks of "boot” training prior to beginning the radio school curriculum. They would soon learn how to march.

Commander Greene, as the new person on the scene, now had his opportunity to add to growing irritations coming from the radio school. He did not miss the chance. Scarcely were the WAVES on board when he complained to President Dykstra about the lengthening of the men's training day. Instructional director Miller had revised the training schedule to accommodate a problem of too many trainees and too few typewriters and code stations, even scheduling class hours as late as 11:00 p.m. Greene desired a normal school day for the men as soon as possible, indicating he would assist in getting the Navy to provide the needed equipment. Dykstra immediately replied that the problem was in the hands of the Navy because it was responsible for providing typewriters to the school. If it would supply the typewriters, the university could then solve the code position shortage and revise the training day.

Increasing frictions also occupied significant space in a letter Dykstra wrote to the Naval District training director. He complained about the "problem of equipment if we are to follow out the Commandant's [Commander Greene] last order, which cuts down the number of hours available for the use of equipment. You will recall that we had spread classes into the evening, a procedure which is not to the liking of the Commandant." Additionally, he complained about the ability of some trainees, stating, “We must also come to grips with the problem of selection...and at an early time transfer those who are so inept that we know they can not possibly become operators. Our local Commandant apparently feels that there must be no such transfers and that our predictions about the failures of men have no place in the program.... It is only fair to the whole situation to say that the School is not running as smoothly as it did, that there are more causes for irritation, and apparently much less understanding of the training problems that are involved in such a School.... If the University is to be actually responsible for the results of a training program, it would seem that the training staff must not lose its authority or have it frittered away.” The District training director replied, “An honest attempt is being made to rectify certain conditions and bring about the proper administration and understanding, all for the best interests of the University and the Navy."

New Leadership for the Radio School

Navy promised assistance for the radio school arrived in late November. Commander Greene received orders to the Naval Training Center at Great Lakes and, on 25 November, Commander Leslie K. Pollard reported for duty as commanding officer. Pollard quickly began taking steps, which were not often to the liking of Dykstra and Miller, to get the situation under control. He believed that the root of the problem was a misunderstanding on the part of the university concerning its instructional responsibilities and discretion. Pollard noted the contract plainly stated that “all matters relating to such instruction, the curriculum, and the supplies and equipment, shall meet the requirements of the Department [of the Navy].” However, this was “apparently not understood by either President Dykstra...or the first commanding officers of the Radio School. When the present Commanding Officer reported here, there was considerable lack of harmony between the Navy and the University which resulted in confusion, dissatisfaction, and inefficiency.” Pollard confronted Dykstra to try to clarify the issue, and Dykstra “was most hostile to what he termed, ‘Just making a hotel out of the University.’” Dykstra's enthusiasm and impatience in December of 1941 were clearly not producing, a year later, the results desired for the university. The key focus of disappointment for Dykstra was that the Radio School was not effectively employing regular faculty.

Pollard, in due course, would remove Miller from the Director of Training position and another professor who was in charge of code instruction. He released a number of civilian clerical assistants, appointed a Navy lieutenant, previously attached to a ship's communication department, as training officer, took steps to augment the number of fleet experienced radiomen on the instructional staff and appointed a University Coordinator who reported to him, not to Dykstra. Thus, Pollard effectively took to himself responsibility for the school and the authority to carry things out. He additionally placed all civilian instructors on a full working day, reducing the number of instructors per student day, thus increasing instructor pay and reducing overall costs per student while increasing the amount of instruction given.

Pollard, a former communications officer afloat, knew what Dykstra increasingly understood. “The training of radiomen may be classified as trade school training. It is very definitely not a university task. This University does not even teach typing. Therefore, the establishment of such training activities as a radio school at a university should be entirely under the control and administration of the Navy.” Pollard credited an eventual standardization of training at radio schools by the Training Division of the Bureau of Naval Personnel as being of considerable value, and he lamented that such guidance was not sooner available. Relations between the Navy and President Dykstra, while improved, remained sensitive through the remainder of Dykstra's presidency.

Under Pollard, things rapidly began to settle down. By December of 1942, the Navy restored a week of training time, earlier taken away, Pollard agreed with Miller that high training standards were appropriate, and the performance of the first WAVES class was excellent in comparison to the men, perhaps because of stricter selection criteria.

The V-12 Program Envisioned

By the fall of 1942, the Navy recognized that the approaching draft of 18 and 19-year-olds seriously threatened the college source of young officer candidates, particularly in light of the failure of V-1 to achieve its hoped-for popularity. The answer to the problem was the V-12 Program.

With the approach of the draft of college students, both the services and institutions of higher education were equally concerned about the potential impact on college male populations. The services needed a continuing supply of college-educated men for officer training programs. The institutions not only desired to aid the war effort but also feared the disastrous consequences that would result from the loss of substantial student numbers., Colleges and universities thus faced the prospect of having to cut faculties to the point of endangering not only their futures but also the nation’s system of higher education. The American Council on Education (ACE) served as the principal spokesman for colleges and universities. ACE representatives spent considerable time in conference with the services and the War Manpower Commission (WMC), discussing the most acceptable use of college and university resources. Spurred by the failure of the V-1 program and also by a direct prod from President Roosevelt, the Navy came to actively explore with ACE the opportunities and imperatives that were the foundation of V-12. By November of 1942, the Navy envisioned a program with these characteristics: employ institutions widely distributed geographically but carefully selected based on facilities and instructional capacity; provide a minimum of military discipline; select students based on a competitive examination; permit the Navy to prescribe the minimum portion of the curricula that would be necessary to ensure production of officers using the present curricular organization of the institutions; not require recruit training as a pre-requisite; call to active duty on 1 July 1943 those enrolled in V-1 and V-7, permitting them several terms of college work inversely proportional to the number of terms completed.

American troops landing North Africa November 1942

The V-12 Program Becomes Defined Late 1942

By November of 1942, the proposal, along with one from the Army, went to the President. Roosevelt added three politically-oriented suggestions: assign state quotas by population; select students in boards composed of a naval officer, a civilian, and an educator; and distribute Army and Navy training among colleges as widely as efficiency would permit (thus, in some instances, “saving the colleges").

The Chairman of WMC published the principles for the selection of civilian institutions. These provided for the establishment of a joint committee composed of nine representatives, three designated by the Secretary of the Navy, three by the Secretary of War, and three by the Chairman of WMC. The joint committee would determine the availability of institutions’ facilities and allocate their use to either the Army or the Navy. The selection method was intended to minimize pressure from individual institutions or political allies.

In December 1942, the Joint Committee prepared a questionnaire to determine the facilities and personnel available in the nation’s colleges and universities and forwarded copies to every institution of higher education. The Committee received about 1,600 replies by the following March. Each service then made tentative selections based on quotas and curricular needs. The Joint Committee had final approval authority. Subsequently came contract negotiations following preliminary inspections conducted by service training directors. Of the 1,600 institutions that responded, the Navy selected 150 for careful review and ultimately granted contracts to 131 for undergraduate V-12 training.

Participating institutions found V-12 to be about as advantageous as did the Navy. In general, the Navy-specified curricula differed only slightly from those they offered before the war. Additionally, a substantial portion of the male on-campus population during the remaining war years was, for these institutions, the result of Navy and Army college programs.

The Navy V-12 Program absorbed the previously existing naval reserve officer college programs, including a large proportion of V-1, virtually all of V-7, all of NROTC, and a portion of aviation V-5 trainees (designated V-12(a)). Thus, V-12 placed many reserve personnel on active duty, retained them in college-student status, and paid tuition, fees, books, room, and board. It permitted a variety of academic programs that would provide prospective officers for duty in the deck, engineering, aviation, medical and dental, supply, aerology, theological specializations, and the Marine Corps. It provided a mechanism to rationalize the services' needs for officer candidates with the competing demands for skilled manpower as represented by the WMC. It provided a means for qualified Navy and Marine Corps enlisted personnel to secure the educational preparation necessary for officer training; it met the administration's desires, as well as those of the ACE and the institutions to save the colleges; it permitted a rational method of staging the flow of officer trainees to Reserve Midshipmen Schools and to the ships and units gradually expanding beyond them; and it offered a means to avoid the draft for those so persuaded.

USS WISCONSIN (BB 64) Under construction Philadelphia Navy Yard

V-12 Students Bowling

1942

February 1942

19 Japanese internment camps established as Roosevelt orders Japanese and Japanese-Americans in Western U.S. to be exiled to “relocation centers,” many in isolated areas, as a reaction to Pearl Harbor and to prevent sabotage

April 1942

9 Major General Edward P. King Jr. surrenders at Bataan, and the largest number of U.S. soldiers ever to surrender are taken captive by the Japanese Army

May 1942

6 U.S. and Filipino troops on the fortress island of Corregidor, in Manila Bay surrender to Japan

June 1942

4 - 6 Within six months of Pearl Harbor, the Battle of Midway is victorious in a five day battle that is the turning point in the war in the Pacific

10 A City of Madison airfield north of downtown is activated by the Army Air Force as Madison Army Airfield and will be closed as an active field in 1945. In 1952 the airport, now conveyed to the city, will be renamed Truax Air Force Base and reactivated.

1942

August 1942

7 U.S. forces in the Pacific take the offensive for the first time with the invasion of the Eastern Solomons islands of Guadalcanal and Tulagi, a six-month campaign

9 Battle of Savo Island - The Imperial Japanese Navy responds to the Solomons offensive and Allied naval forces screening the Allied landing force suffer one of their most severe losses of the Pacific in a night surface attack

November 1942

8 Amphibious landing of U.S. and British forces land in French North Africa, Algeria and Morocco